Hive Beetle Traps: A Complete Timeline

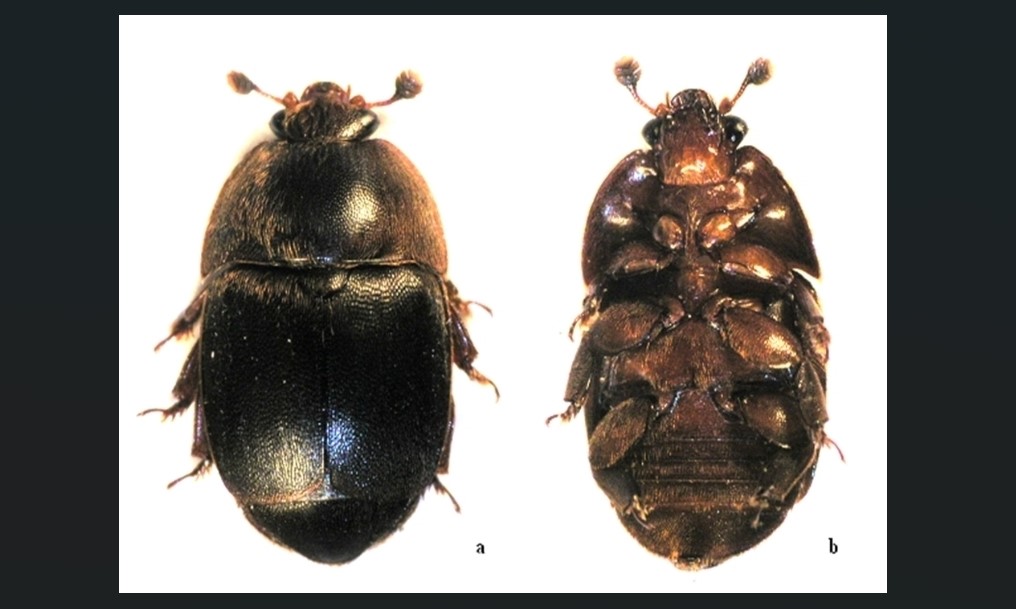

Photo: James D. Ellis, University of Florida / © Bugwood.org, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

You check your trap and count 47 beetles trapped in oil. That's 47 beetles your colony wasn't strong enough to contain on its own. The trap worked, which means it was necessary, which means there's a problem. The beetles you're looking at represent a specific point in a timeline that's already running.Small hive beetle infestations operate on predictable cycles, and a full trap indicates where your colony sits within those cycles. Understanding the timeline tells you what's happening now, what happened two weeks ago, and what's coming in the next month if conditions remain unchanged.

The 24-Hour Egg Clock

Female beetles begin laying eggs within 24 hours of entering a hive. A full trap today means beetles were entering your hive yesterday, and they were likely laying eggs before your trap caught them. Female beetles lay 10-30 eggs in clusters, tucked into crevices, cracks, or directly into capped brood cells where bees can't easily detect them.

Each female carries capacity for 1,000-2,000 eggs across her six-month lifespan. The beetles in your trap represent reproductive potential that's partially expressed. Some laid eggs before entering the trap. Some were caught before mating. The ratio between those two groups determines your current infestation severity.

Temperature drives the egg timeline. Between 60-112°F, eggs hatch in 2-4 days, most commonly within 72 hours. Below 60°F, development slows or stops. Above 112°F, eggs desiccate. If your trap filled during active foraging season with temperatures above 70°F, assume eggs laid three days ago are hatching today. If your trap filled during cooler weather, that timeline extends to 4-6 days.

The 10-Day Larval Countdown

Larvae emerge from eggs and immediately begin tunneling through comb. They're after honey, pollen, and bee brood. They defecate as they move, releasing yeast that ferments honey and creates the characteristic slime associated with beetle infestation. This is the most damaging life stage.

Larvae develop through three instars over 10-16 days under optimal conditions (68-86°F). Development can extend to 29 days at cooler temperatures or with limited food. The larvae in your hive right now, hatched from eggs laid when those trapped beetles were still mobile, are between days 3 and 13 of this cycle.

By day 10, larvae enter "wandering phase." They stop feeding and seek exit points. They move toward light, congregate on bottom boards, and leave the hive at dusk to burrow into soil. A single heavily infested hive can produce tens of thousands of wandering larvae, all exiting within a narrow timeframe.

Here's the critical window: If you caught beetles in your trap today, larvae from their earlier egg-laying are 5-8 days into development. You have 2-8 days before those larvae complete feeding and exit the hive. After they exit, you can't stop them.

The 3-6 Week Underground Gap

Larvae burrow 2-8 inches underground, usually within 36 inches of the hive. They construct smooth-walled pupation chambers and transform over 3-6 weeks. During summer with warm soil temperatures, this period runs closer to 21 days. During fall or in cooler soil, pupation extends to 8-12 weeks. At temperatures below 50°F, pupation can take 100 days.

While larvae pupate underground, you can't detect them in the hive. You're operating blind. The soil around your hives holds the next generation, and you won't know how many until adults emerge and reenter the colony.

Adult beetles emerge ready to fly. They can travel up to 4.3 miles searching for hives, guided by scent. They detect honey, pollen, and bee pheromones from considerable distances. Beetles prefer weak hives during warm months when they need abundant resources quickly. During winter, they target strong hives for warmth.

That 3-6 week underground gap creates a delayed feedback loop. If you saw a full trap today and took corrective action, you'll still face a surge of newly emerged adults in three weeks regardless. Those adults come from larvae that left the hive before you implemented changes.

The Strength Assessment Window

A full trap provides specific diagnostic information about colony strength. Strong colonies with robust populations and low varroa mite counts defend effectively against beetles. They chase beetles constantly, forcing them into corners and crevices. Beetles hide rather than feed and reproduce. The bees create "prisons" using propolis, containing beetles away from brood and food stores.

When bees can't maintain this defensive pressure, beetles move freely. They access comb, lay eggs without harassment, and feed openly. The trap fills because beetles are running from bees, but filling the trap means there are enough beetles to overwhelm bee defenses.

Commercial beekeepers in warm climates report that colonies with varroa mite counts below treatment thresholds rarely show beetle problems, even in high-beetle-pressure areas. One operation saw 75% colony losses to beetles before implementing mite management. After reducing mite loads, beetle losses dropped to near zero while beetle presence remained constant. The beetles were always there. The difference was whether bees could defend.

If your trap filled, assess mite loads immediately. A full beetle trap combined with elevated mite counts indicates your bees are fighting a two-front war they're losing. Addressing mites often resolves beetle pressure without additional beetle-specific interventions.

The Population Math

Beetle populations grow exponentially under favorable conditions. Start with that full trap of 47 beetles. If half were mated females and each laid 100 eggs before being trapped, that's 2,350 eggs. At 80% hatch rate (typical under good conditions), that's 1,880 larvae. If 70% of larvae successfully pupate (typical survival rate), that's 1,316 new adults emerging 4-8 weeks from when those eggs were laid.

But those 47 beetles weren't the only ones in your hive. They were the ones that ran from bees into your trap. Trapped beetles represent a fraction of total population - the ones your bees chased toward trap entrances rather than toward other hiding spots.

Research examining trap efficiency suggests that in-hive traps catch 40-60% of mobile adult beetles over a week-long period in moderately infested hives. If you caught 47 beetles, likely 30-50 additional beetles are still in the hive, hiding in crevices, under frames, or in clusters of bees.

The timeline runs independently for each female's reproductive output. Eggs don't hatch simultaneously. Larvae don't all exit on the same day. Adults don't all emerge together. You're facing overlapping waves of development, creating continuous pressure rather than discrete events.

The Geography of Pupation

Beetle larvae pupate in soil, preferring moist ground with moderate temperature. They burrow primarily within three feet of the hive entrance, though some travel up to 200 yards searching for suitable soil. Larvae can survive up to 60 days in wandering phase without food while searching for pupation sites.

This dispersal pattern affects timeline planning. If your hive sits on well-drained soil in full sun, fewer larvae successfully pupate. High temperatures at the soil surface kill larvae before they burrow deep enough. Dry soil inhibits pupation. UV exposure during their dusk exit walk causes mortality.

Hives on grass, particularly in shaded locations with moist soil, provide ideal pupation conditions. Larvae exit, burrow immediately, and pupate successfully. These sites maintain higher beetle pressure because the complete lifecycle occurs within feet of the colony.

Some beekeepers place hives on gravel, concrete pads, or landscape fabric specifically to disrupt this soil-pupation dependency. Larvae exit the hive but can't complete development. Over time, this breaks the local beetle population cycle. However, this only prevents locally-generated populations. Beetles are strong fliers and continuously arrive from other locations.

The Seasonal Pressure Shift

Beetle pressure follows temperature patterns. Peak reproductive activity occurs April through September in southern states, with narrower windows in northern locations. During these months, the complete egg-to-adult cycle can run as fast as 23 days. A colony can face six overlapping beetle generations in a single season under ideal conditions.

Fall creates a particularly dangerous window. Ambient temperatures remain above 60°F, supporting beetle reproduction, but colony populations decline naturally as bees prepare for winter. The ratio of beetles to bees shifts unfavorably. Colonies with adequate bee populations in July become beetle-vulnerable by September despite having fewer total beetles.

This is when traps fill unexpectedly. Beekeepers check hives in late summer, see a full trap, and assume beetle populations surged. Often, beetle numbers remained constant while bee numbers dropped. The trap filled because bees could no longer maintain defensive coverage across the hive's interior.

Winter provides relief only in genuinely cold climates. Beetles overwinter as adults within the cluster. They can survive months without reproducing, waiting for spring temperatures to trigger egg-laying. A colony entering winter with 20 beetles will exit spring with 20 beetles plus whatever adults emerged from fall pupation. Then reproduction accelerates immediately.

The Intervention Timeline

A full trap today triggers specific action windows based on lifecycle stage timing:

Days 0-3: Empty the trap, assess colony strength, check varroa mite counts, evaluate whether the colony has adequate bee coverage for all comb. If bees don't cover all frames, remove empty or partially filled frames to reduce interior space beetles can exploit.

Days 3-7: Larvae from pre-trap eggs are feeding. Inspect frames for larval damage, checking particularly in corners and along frame edges where bee coverage is thinnest. Look for the slime - fermented honey with yeast smell, often described as rotting oranges.

Days 7-14: Wandering-phase larvae exit at dusk. Monitor ground around the hive for larvae. This is when ground treatments (diatomaceous earth spread in a 2-3 foot radius) can intercept larvae before pupation. This window represents your last chance to interrupt the current generation before they become adults.

Weeks 3-6: New adults emerge and seek hives. If you corrected colony weakness, reduced mite loads, and removed excess space, returning adults face stronger defenses. They still enter the hive, but bees contain them. Traps catch these returning adults, preventing reproduction.

Weeks 6-8: Second-generation eggs hatch from any returning adults that successfully reproduced. This is when you evaluate whether your interventions worked. If traps remain light or empty, colony defenses are functioning. If traps refill, the intervention timeline cycles again.

The Honey House Connection

Full traps often correlate with extraction timing. Beetle adults and larvae invade supers of honey stored in extraction facilities. A single adult beetle finding unprotected comb can produce hundreds of larvae in days. Those larvae consume and ferment honey, destroying entire supers.

Beekeepers who notice full traps during or immediately after honey harvest often discover the infestation originated in stored supers, not in active hives. Beetles reproduce in honey house conditions, then adults fly to nearby hives. The hive infestation is secondary to the storage facility problem.

Supers should be extracted within 48 hours of removal from hives. After 48 hours, any beetle eggs laid on the comb hatch into larvae. After 5-7 days, those larvae cause visible damage. After 10 days, supers may be unsalvageable.

If extraction delays are unavoidable, freeze supers at 10°F for 12 hours (counting from when frames reach temperature, not when they enter the freezer). This kills all beetle life stages. Alternatively, store in sealed containers or rooms maintaining humidity below 50%, which prevents egg hatching.

The Slime Threshold

Beetle larvae create slime - fermented honey mixed with their frass and the yeast they carry. Once slime appears, damage is severe. Bees won't accept frames with slime. Honey contaminated with slime is unfit for human consumption and should never be bottled or mixed with clean honey.

Slime represents population breakthrough. Individual beetles produce manageable larvae counts. When 50-100 adult beetles reproduce simultaneously, larval populations explode beyond what any colony can contain. At that point, the hive often absconds. Bees leave rather than attempt to clean and rebuild.

A full trap today, combined with any sign of slime, indicates you're 10-14 days into a major infestation. The trap caught recent arrivals, but established populations already reproduced. The timeline for this colony is significantly compressed. You have days, not weeks, to prevent abandonment.

The smell accompanies slime - fermented honey has a specific odor that alerts beekeepers even before opening the hive. If your full trap coincided with unusual odors around the hive entrance, assume larval populations are already substantial. Immediate frame inspection is required.

The Equipment Question

Beetle traps come in multiple designs: oil-filled reservoir traps between frames, screened bottom boards with oil trays, entrance traps, and top traps under the outer cover. A full trap demonstrates that particular design successfully intercepted beetles in that hive configuration.

But trap placement matters for timeline assessment. Bottom board traps catch beetles that fall through frames or are knocked down by bees. These traps filling indicates aggressive bee response to beetles already inside the hive. Frame-top traps catch beetles running across the top bars, usually newly-entered adults seeking hiding spots. Entrance traps catch beetles attempting to enter, representing external pressure before establishment.

Where your trap caught beetles tells you which stage of infestation you're addressing. Full entrance traps without corresponding internal trap activity suggest strong colony defense is preventing establishment. Full internal traps combined with light entrance traps indicate established populations reproducing inside the hive. Full traps at all locations indicate overwhelming pressure that exceeds colony defensive capacity.

What the Numbers Actually Mean

Here's what a trap containing 47 beetles tells you:

Your colony faced significant beetle pressure in the past week. Those beetles came from somewhere - either your hive's own pupation sites or nearby hives and apiaries. They weren't deterred by entrance guards, which means entrance activity was high enough that beetles slipped past during traffic.

Your bees chased beetles actively enough to force them toward and into the trap. This indicates some defensive capacity, but not enough to exclude beetles entirely. The bees are trying. They're not succeeding.

If female beetles were mated (likely for 70-80% of trapped adults), each laid some eggs before capture. Assume 30-40 eggs per female on average, accounting for time in hive before being trapped. That's 600-1,000 eggs from that specific batch of trapped beetles.

Those eggs are hatching or have hatched. The larvae are feeding or will begin feeding in 2-4 days depending on trap date and temperature. You're looking at 500-800 larvae (accounting for egg mortality) beginning their damage cycle.

In 10-16 days, those larvae exit and pupate. In 3-6 weeks after that, 400-650 new adult beetles emerge (accounting for pupation mortality). Your trap caught one generation. The next generation is already developing. The third generation is gestating underground.

You're not looking at a single event. You're looking at a continuous production line of beetle generations, each overlapping the previous one by 2-3 weeks. The trap interrupted one day's worth of beetle activity in a cycle that's been running for at least a month and will continue running until you change the conditions that allow it.

The timeline isn't theoretical. It's happening. The beetles you trapped yesterday laid eggs three days ago. Those eggs are larvae today. Those larvae will be adults in five weeks. The trap bought you time by removing reproductive capacity, but only about 40% of it based on trap efficiency research. The other 60% of beetles avoided the trap.

You have a window. How long that window stays open depends on what you do in the next 72 hours, not the next month. Because in a month, the next generation emerges, and the timeline resets with even higher population pressure than before.

The beetles don't care about your timeline. They're already on theirs.