Almond Pollination Contracts: What's Required

Every February, something happens in California that most people never think about: roughly 90% of America's commercial honey bee colonies converge on the Central Valley to pollinate 1.3 million acres of almond trees.

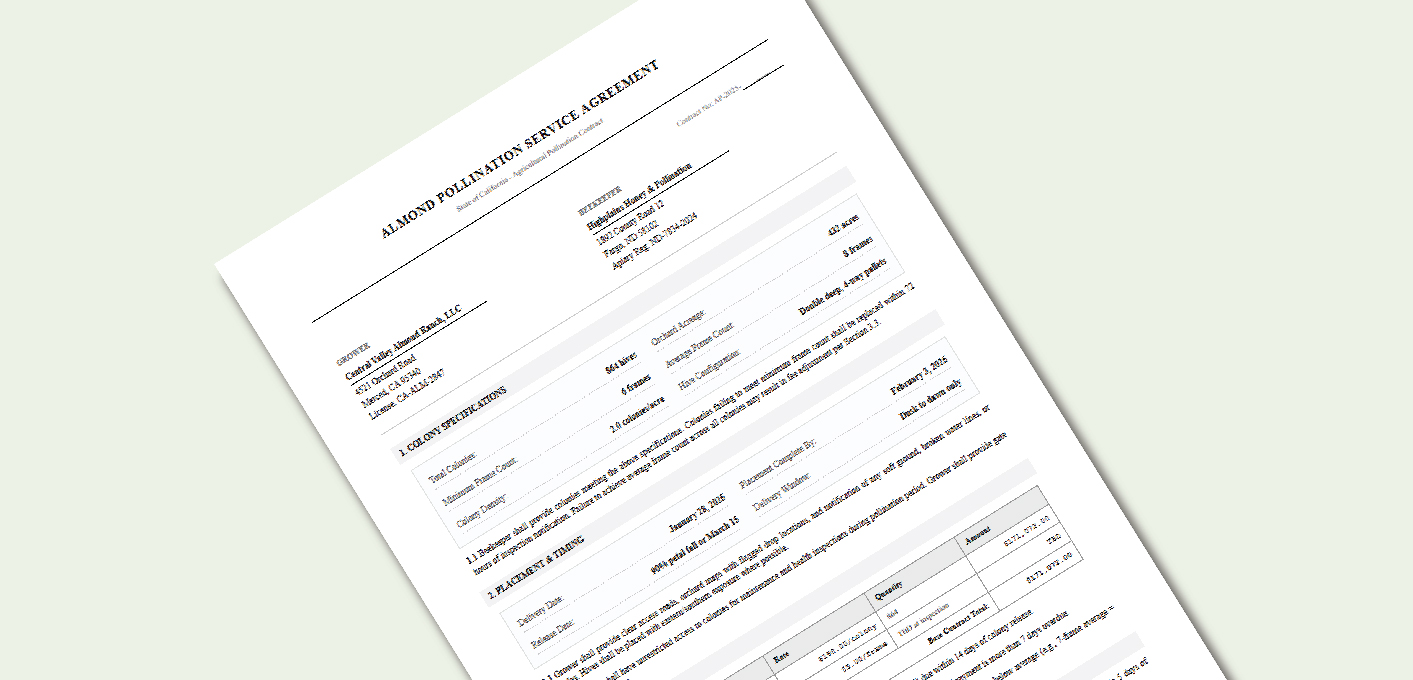

This isn't a spontaneous migration. It's orchestrated through contracts - thousands of individual agreements between almond growers and beekeepers that specify, in remarkable detail, exactly what "renting bees" actually means.

These contracts reveal an entire parallel economy operating beneath the surface of American agriculture. And the specifics are fascinating.

The Basic Transaction

At its core, an almond pollination contract is a rental agreement. A grower pays a beekeeper to place colonies in their orchard during bloom, typically mid-February through mid-March. The bees do their thing, the trees get pollinated, nuts develop, everyone goes home.

Current rates run $180-$220 per colony, with the average hovering around $196-$210 depending on colony strength requirements. For context, that means a 500-acre almond operation at two hives per acre pays roughly $200,000 just to rent bees for three weeks.

That's just the base transaction. The contract itself addresses dozens of variables that can make or break both parties.

Frame Count: The Central Negotiation

The most important number in any pollination contract isn't the price - it's the frame count.

A "frame" in this context means a frame of bees inside the hive. When you open a standard Langstroth hive, you see 10 frames hanging vertically. A strong colony might have bees covering 10-12 of those frames across two boxes. A weak colony might have bees covering only 4-5 frames.

The industry standard is an 8-frame average with a 6-frame minimum. This means all colonies placed in an orchard should average eight frames of bees, and no individual colony should fall below six frames.

Why does this matter so much? Because frame count directly determines pollination capacity. An 8-frame colony has roughly 6,400 "field force" bees - workers that actively leave the hive to forage. A 4-frame colony has maybe 800 field force bees. You'd need seven or eight weak colonies to match the pollination output of one strong colony.

One California broker put it memorably: paying for weak hives is "like paying for 1,000 gallons of fuel and receiving only 800 gallons."

Different contracts specify different requirements. The 2026 survey data breaks down like this:

- 4-6 frame average: $178-$188 per colony

- 7-9 frame average: $196-$198 per colony

- 10-12 frame average: $205-$208 per colony

Those price differences look modest until you multiply by colony count. A grower contracting for 1,000 colonies at the 6-frame tier versus the 8-frame tier saves roughly $20,000 - but potentially receives significantly less effective pollination.

The Inspection Protocol

Contracts specify how colony strength gets verified. This is where things get procedural.

Third-party inspectors - often county agricultural officials or independent inspection services - randomly select about 10-15% of colonies in each orchard for grading. The inspection happens after delivery but before full bloom, giving beekeepers time to substitute weak colonies if needed.

The grading method matters. Inexperienced inspectors sometimes just pop the lid and count frames that appear covered with bees. This overestimates strength because bees naturally move toward the top of the hive. The accurate method involves tipping both boxes off the bottom board and examining the underside of frames in the lower box, then cracking the boxes apart to count coverage on both sides of the break.

Roughly 61% of growers never pay for third-party inspections. About 28% pay for annual inspections. The remaining 11% only inspect in years when they suspect colony strength is low.

The contract should specify who pays for inspection (usually the grower), when it happens, the temperature and time of day (bees cluster tightly in cold conditions, making accurate counts difficult), and what happens if colonies fail to meet specifications.

Standard remedies for substandard colonies include:

- Beekeeper has 3-5 days to bring additional colonies to raise the average

- Fee reduction proportional to the shortfall

- Right to dispute the inspection and request a second opinion from a mutually agreed inspector

That last point matters more than you'd think. Surprisingly, many inspectors aren't actually beekeepers and may not fully understand colony grading nuances.

Timing and Placement

Contracts specify when colonies arrive and where they go.

The standard delivery window is shortly before bloom begins - typically late January for California almonds. University of California recommendations suggest placing hives at about 10% bloom, when there's enough open flower to hold bees in the orchard rather than having them fly elsewhere seeking forage.

Placement specifications might include:

- Eastern and southern exposures preferred (morning sun warms hives and gets bees flying earlier)

- Distance from orchard edges

- Access routes for beekeeper service visits

- Clustering patterns (typically 12-20 hives per "drop" location)

- GPS coordinates or maps showing exact placement

Growers agree to provide clear drop-off areas with maintained access roads. That sounds obvious until you've tried delivering 400 colonies at night (bees travel best after dark when they're clustered) and discovered the orchard entrance is blocked by irrigation equipment.

Removal timing is equally specified. The standard is release at 90% petal fall on the latest-blooming variety. Beekeepers want out as soon as pollination work is done because they have other commitments - Washington apples, Maine blueberries, or simply getting home to start honey production season. Growers want maximum pollination coverage.

The contract should establish who makes the call and how disputes are resolved.

The Pesticide Clauses

Here's where relationships get tested.

Almond orchards require pest management. Beekeepers understandably want their colonies protected from chemical exposure. These interests don't always align smoothly.

Survey data shows that 54% of beekeepers have at least one pollination agreement containing pesticide-related language. The most common provisions:

- Grower will not apply pesticides when bees are actively foraging (33% of contracts)

- Grower will not tank-mix insecticides with fungicides during bloom (a combination shown to be particularly harmful)

- Applications limited to night hours when bees are in the hive

- Beekeeper notified 24-48 hours before any application

- Compensation specified if colonies must be moved due to pesticide application

- Compensation specified if colonies are damaged by pesticides

About 11-12% of beekeepers have contracts specifying reimbursement if colonies are damaged or must be relocated due to pesticide applications.

The numbers on actual exposure are sobering. In a recent survey of commercial beekeepers who pollinate almonds, 19% reported lethal pesticide exposure to their colonies during almond pollination in the previous two years. Another 56% reported sublethal exposure - meaning bees were affected but colonies survived.

Sublethal exposure sounds less alarming than it is. Effects may not appear until after bloom, when the hive is back home and the beekeeper can't prove the damage occurred in California.

Research suggests beekeepers value pesticide protection clauses highly. One study found beekeepers would accept roughly $8 less per colony - a 4% discount - in exchange for guaranteed restrictions on tank-mixing and night-only fungicide applications. On a 5,700-colony operation (the average survey respondent size), that's $45,600 worth of value placed on pesticide protection.

Water and Access

Minor provisions that cause major problems when overlooked.

Contracts should specify water availability. Bees need abundant water - they use it for cooling the hive and diluting honey to feed larvae. If no natural water source exists within half a mile, the grower agrees to provide potable water containers.

After pesticide applications, any water sources in the orchard need to be covered or replaced. Bees don't know the water collected pesticide runoff.

Beekeeper access rights seem straightforward but require specification. Beekeepers need to enter orchards for colony maintenance, health checks, and feeding. The contract should confirm this access exists and that the grower assumes responsibility for any crop damage from vehicles using agreed routes.

Some contracts go further and specify that the grower "agrees not to touch, open, move, disturb or otherwise harass any beehives without the express written permission of the beekeeper." That language exists because growers have been known to do exactly those things, sometimes with good intentions (moving a hive away from a spray area) and sometimes not.

Payment Terms

Standard payment structure involves some amount upfront - typically 30-50% on contract signing or colony delivery - with the balance due after pollination concludes.

The deposit serves multiple purposes. It locks in the beekeeper's commitment during a period when other growers might offer higher rates. It provides working capital for beekeepers who've spent months feeding and medicating colonies to reach contract strength. And it demonstrates good faith.

Survey data indicates 44% of beekeepers have at least one contract paying a portion in advance. Among those, 21% receive 30% or less upfront, while 19% receive over 40% before colony placement.

Growers benefit from advance payment too. Research shows beekeepers value prepayment at roughly 40% of the fee - meaning they might accept a lower per-colony rate in exchange for guaranteed early cash flow. A grower willing and able to pay half upfront might negotiate meaningful savings.

The Broker Question

Many growers and beekeepers work through intermediaries called pollination brokers.

The Almond Board of California lists over 40 brokers in their pollination directory. These companies connect growers needing bees with beekeepers seeking placement, handling contracts, logistics, and often colony management during pollination.

Brokers offer real value. A grower gets guaranteed pollination service - if one beekeeper's colonies die en route, the broker substitutes colonies from another operation. A beekeeper gets guaranteed payment - the broker assumes the risk of grower default.

Broker fees typically range from $2 to $20 per colony, paid by the beekeeper (reducing their net rate) or the grower (increasing their gross cost). Some brokers provide additional services: holding yards where colonies can be staged before orchard placement, feeding and medication programs, inspection coordination.

The 2015 survey found 53% of growers contracted directly with beekeepers, 44% used a combination of direct contracts and brokers, and 3% worked exclusively through brokers.

Interestingly, one-third of growers who used brokers couldn't say how many individual beekeepers supplied their colonies. The broker handled everything; the grower just received bees.

Colony Security

Hive theft has become a significant contract consideration.

California experienced an 87% increase in reported hive thefts between 2013 and 2024. In 2023 alone, some 2,300 hives were reported stolen. The California State Beekeepers' Association values stolen hives at a minimum of $350 each - and when you factor in replacement costs and lost productivity, the damage can reach $1,000 per hive for commercial operations.

Contracts increasingly address security. Provisions might include:

- Grower provides locked gate access to orchard

- Grower patrols orchard regularly during pollination

- Beekeeper provides contact information on hive boxes

- Both parties agree to report suspicious activity immediately

Some beekeepers now install GPS trackers in hives - a $10-20 investment that has led to recovered equipment in several high-profile thefts. Cameras, motion sensors, and AirTags have all entered the anti-theft toolkit.

The dynamic is complicated. Thieves are often beekeepers themselves (or people with beekeeping knowledge and equipment), stealing colonies to fulfill their own pollination contracts. The stolen hives get rebranded, relocated, and rented to unsuspecting growers.

Growers are encouraged to verify that incoming colonies actually belong to their contracted beekeeper. Most hives have identifying names, brands, or markers. If something looks wrong, the contract should specify reporting procedures.

Crop Insurance Implications

Here's where contracts intersect with federal policy.

Most California almond acreage is insured through USDA Risk Management Agency programs. To collect indemnities when crops fail, growers must demonstrate they followed required production practices - including adequate pollination.

The current crop insurance standard requires a minimum of 12 "active frames" of bees per acre. That can be satisfied with:

- Two colonies averaging 6 frames each

- 1.5 colonies averaging 8 frames each

- One colony averaging 12 frames

This flexibility matters enormously. Growers who historically used two 8-frame colonies per acre (16 frames total) could potentially reduce to 1.5 colonies per acre at the same frame count and stay compliant while saving roughly $103 per acre on pollination fees.

The catch: deviating from established practices invites scrutiny if a crop failure occurs. Inadequate pollination is explicitly not an insurable cause of loss. Adjusters verify pollination practices early when claims are filed.

Smart contracts explicitly reference crop insurance compliance and specify that both parties understand the minimum frame requirements.

What Gets Left Out

Handshake agreements remain common, especially in long-standing relationships. Some beekeepers and growers have worked together for decades, adjusting terms informally each year without written contracts.

Economics research calls these "relational contracts" - agreements that work because the ongoing relationship is worth more than any short-term gain from cheating. When your beekeeper's father delivered bees to your father's orchard, formal contracts can feel almost insulting.

But as colony values increase and pollination fees approach $200+ per hive, formality increases. The survey data shows written contracts are becoming standard.

Elements frequently omitted from contracts that probably should be included:

- What happens if the beekeeper provides colonies from multiple geographic sources (disease transmission concerns)

- Who carries insurance and what it covers

- Force majeure provisions (what if a hurricane kills colonies en route?)

- Antibiotic and treatment disclosure (some growers want documentation of chemical-free colonies)

The Market Context

Understanding contracts requires understanding the market.

California almonds need roughly 2.6-2.8 million honey bee colonies every February. The total US colony count on January 1 is approximately 2.7 million. The math is obvious: almond pollination requires nearly every commercial colony in America.

This creates a seller's market that would normally push prices dramatically higher. Prices have risen - from under $50 per colony two decades ago to $200+ today - but the relationship is complicated by mutual dependency.

Almond growers absolutely need bees. But beekeepers absolutely need almond income. For many commercial operations, almond pollination generates 65-70% of annual revenue. Honey production, once the primary income source, now plays second fiddle to pollination services.

This mutual dependency keeps negotiations functional despite the statistical imbalance. Growers who squeeze beekeepers too hard find their regular suppliers committed elsewhere next year. Beekeepers who demand unreasonable rates find growers willing to accept weaker colonies from competitors.

The contract is where this ongoing negotiation gets formalized.

Practical Notes

For growers entering pollination contracts:

Verify beekeeper reputation before signing. Talk to other growers who've used them. Check if they're registered with the county agricultural commissioner. Ask for references and actually call them.

Establish communication protocols in writing. Know who to call if hives arrive late, if you need to spray, if you observe problems. Don't assume anything.

Understand exactly what you're paying for. Frame count specifications, inspection procedures, and remedies for shortfalls should be explicit.

For beekeepers seeking California placement:

Document everything. Photograph colonies before shipment, during inspection, and at removal. Keep feeding and treatment records. These become essential if disputes arise.

Register hive locations with county authorities. This is required and also provides protection if colonies are stolen.

Negotiate pesticide protections. Research suggests growers are increasingly willing to make accommodations - and the $8-per-colony discount you might offer in exchange is worth the protection.

Consider broker relationships carefully. Brokers add cost but reduce risk. For first-time California operations, the guidance might be worth the fee.

The Bigger Picture

Pollination contracts are legal documents, but they're also relationship documents. The best ones reflect genuine understanding between parties who recognize their mutual dependency.

California's almond industry wouldn't exist without mobile beekeepers willing to truck colonies across the country. American commercial beekeeping wouldn't be economically viable without almond pollination income.

The contracts formalize this symbiosis - specifying frames and fees, schedules and specifications - while leaving room for the trust and flexibility that make agricultural partnerships work.

Understanding what's actually in these contracts reveals how the broader system functions. The $200 per-colony fee isn't arbitrary. It reflects supply constraints, mortality rates, transportation costs, competition for placement, and decades of negotiation between industries that literally cannot survive without each other.

Every almond you eat represents a contractual agreement between someone who grows trees and someone who keeps bees. The specifics matter more than most people imagine.